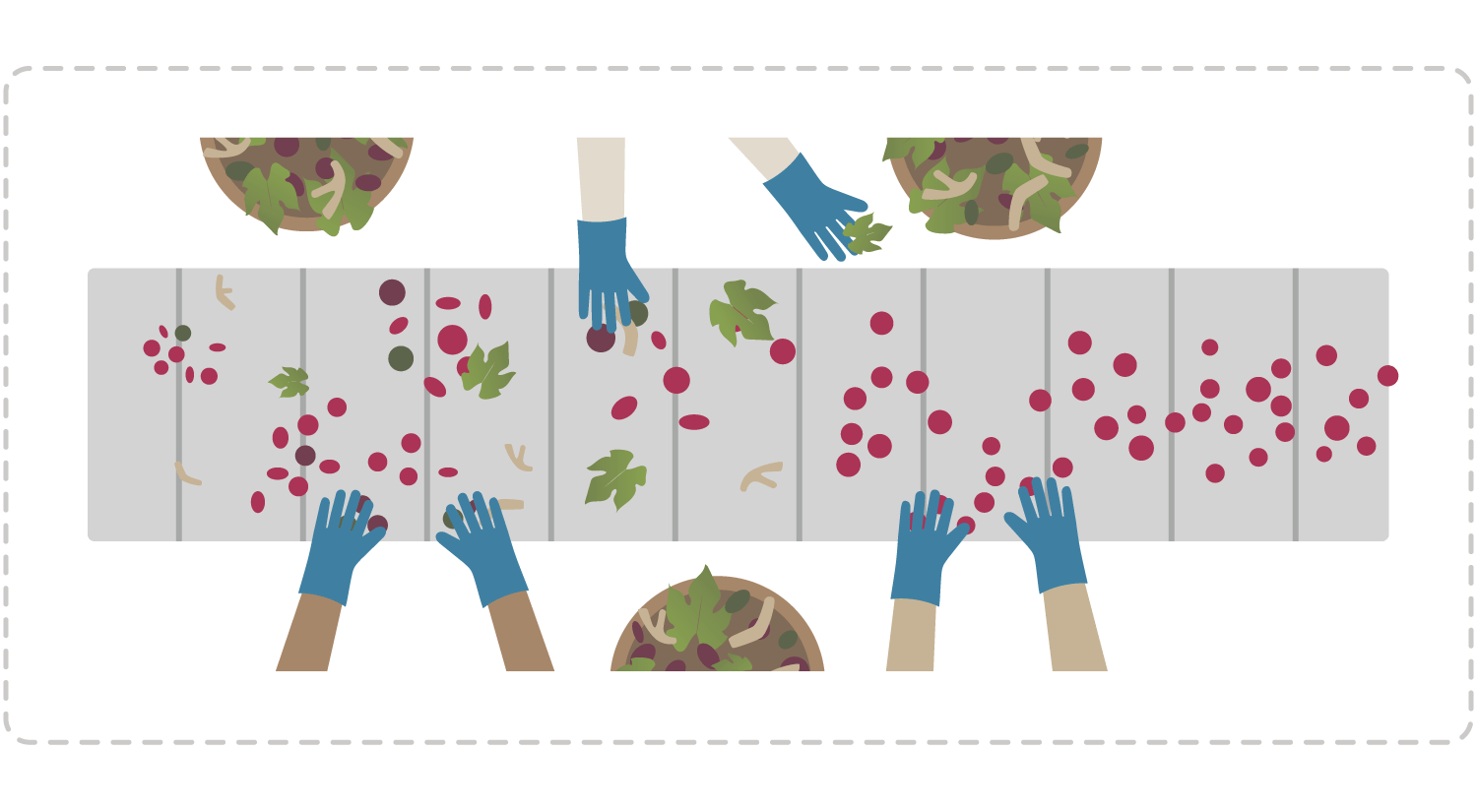

The art and science of winemaking has been around for thousands of years. Each winemaker guides the process in different ways — from pressing wine with your feet to using complex machinery. Most wine is crafted by using the same six steps: harvest, crush, press, ferment, age and bottle.

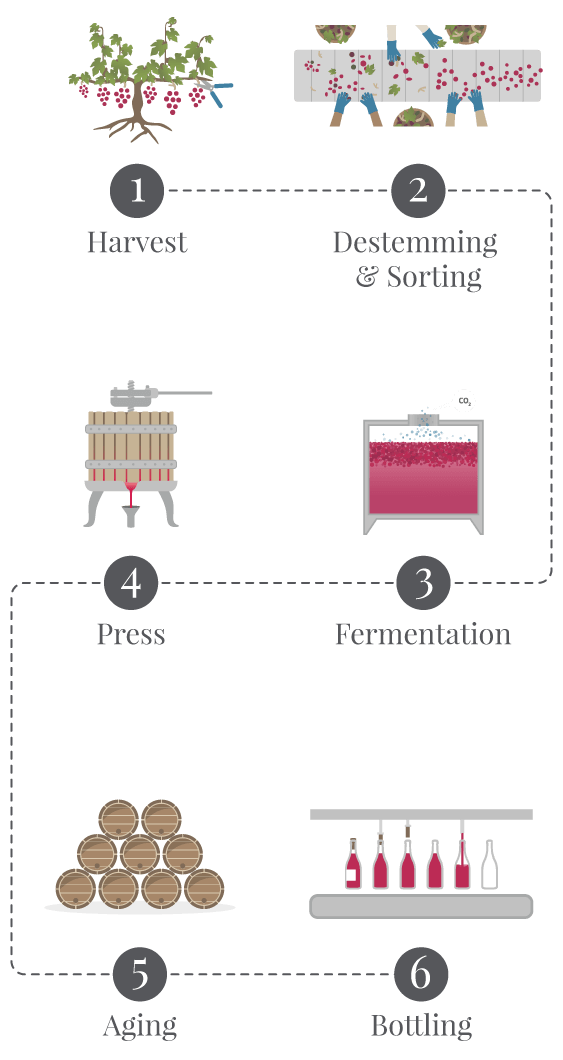

The moment the grapes are picked from the vines determines the wine's acidity, sweetness and flavor. When to pick the grape is an age-old question. Wait longer for the sun to give one last sweet boost to the fruit? Wait too long and have rain or weather ruin a crop?

Harvest season, or "the crush" in the Northern Hemisphere, typically falls between August and October. In the Southern Hemisphere, it's between February and April. Harvesting is done by hand or mechanically. Once picked, the bunches are taken to the winery and sorted.

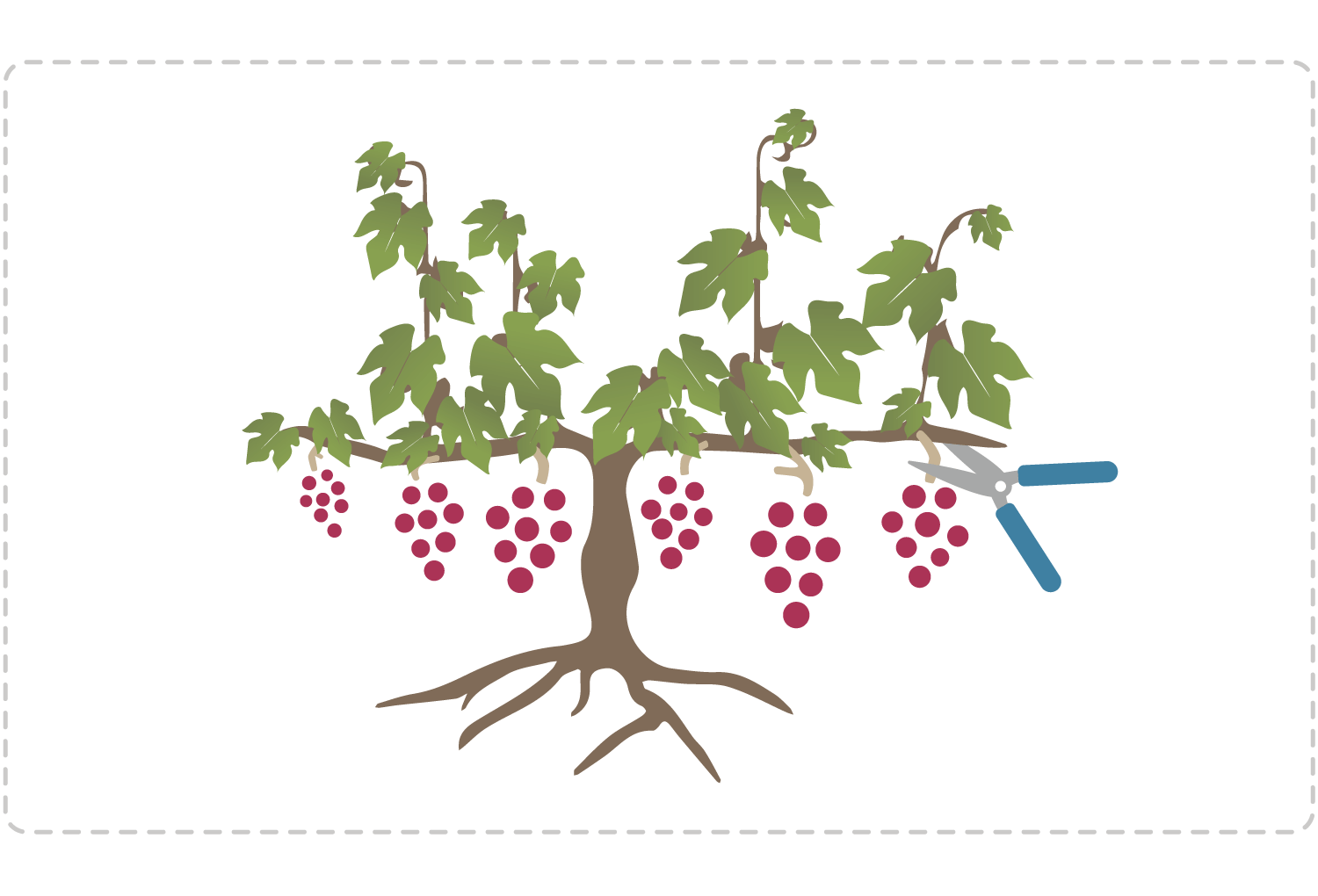

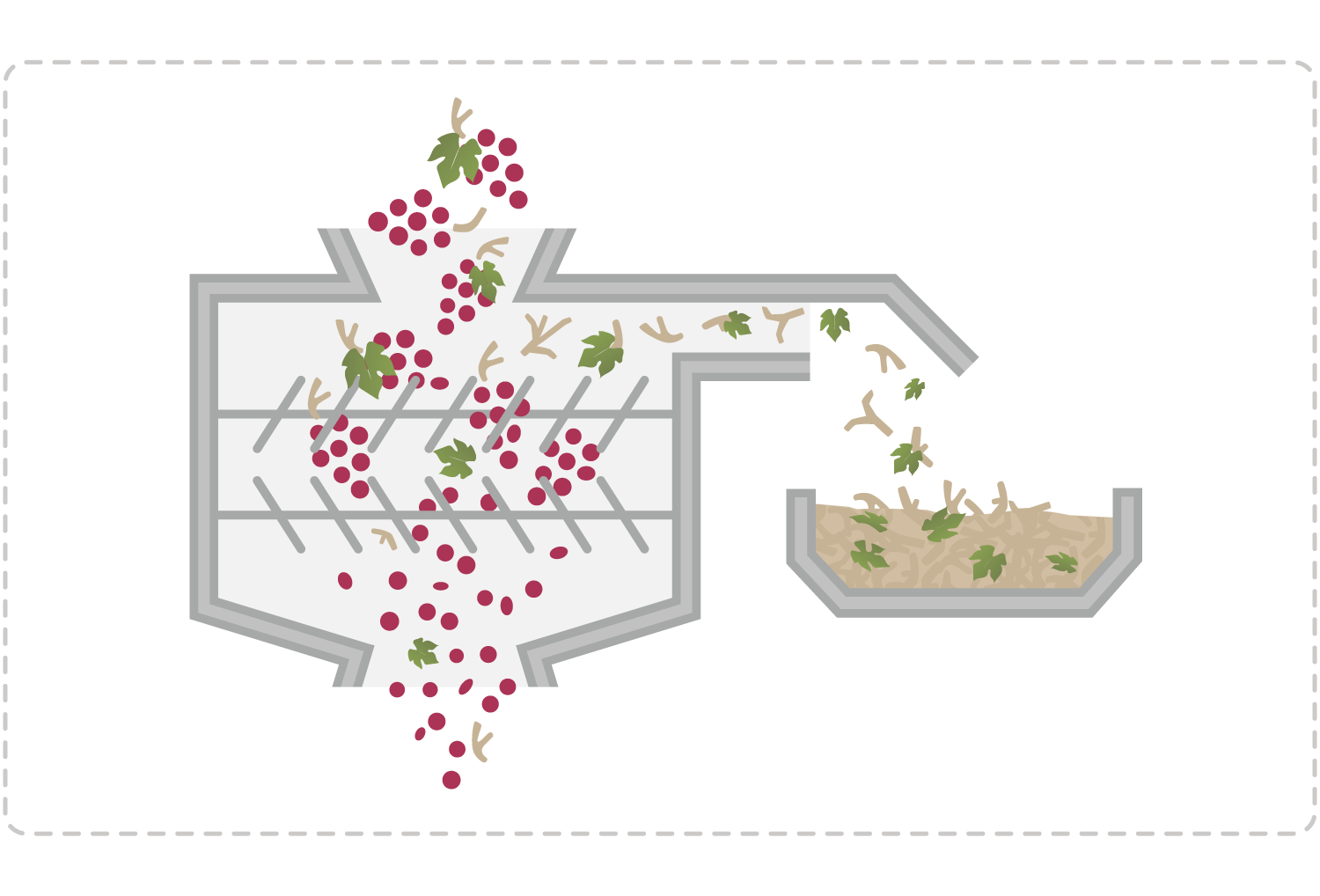

Once sorted, grape bunches need to be destemmed and crushed. Sophisticated machinery can remove stems without damaging the fruit, and the grapes can then be crushed. In white wines, grapes move from crushing to pressing immediately, with little or no contact between the grape skins and juice. For red wine, grape pressing usually doesn't take place until after fermentation. Rosé starts as a red wine, but the juice is pressed from the fruit after a short time in contact with the skins. This contact with the skins creates the subtle pink or salmon hue of the wine.

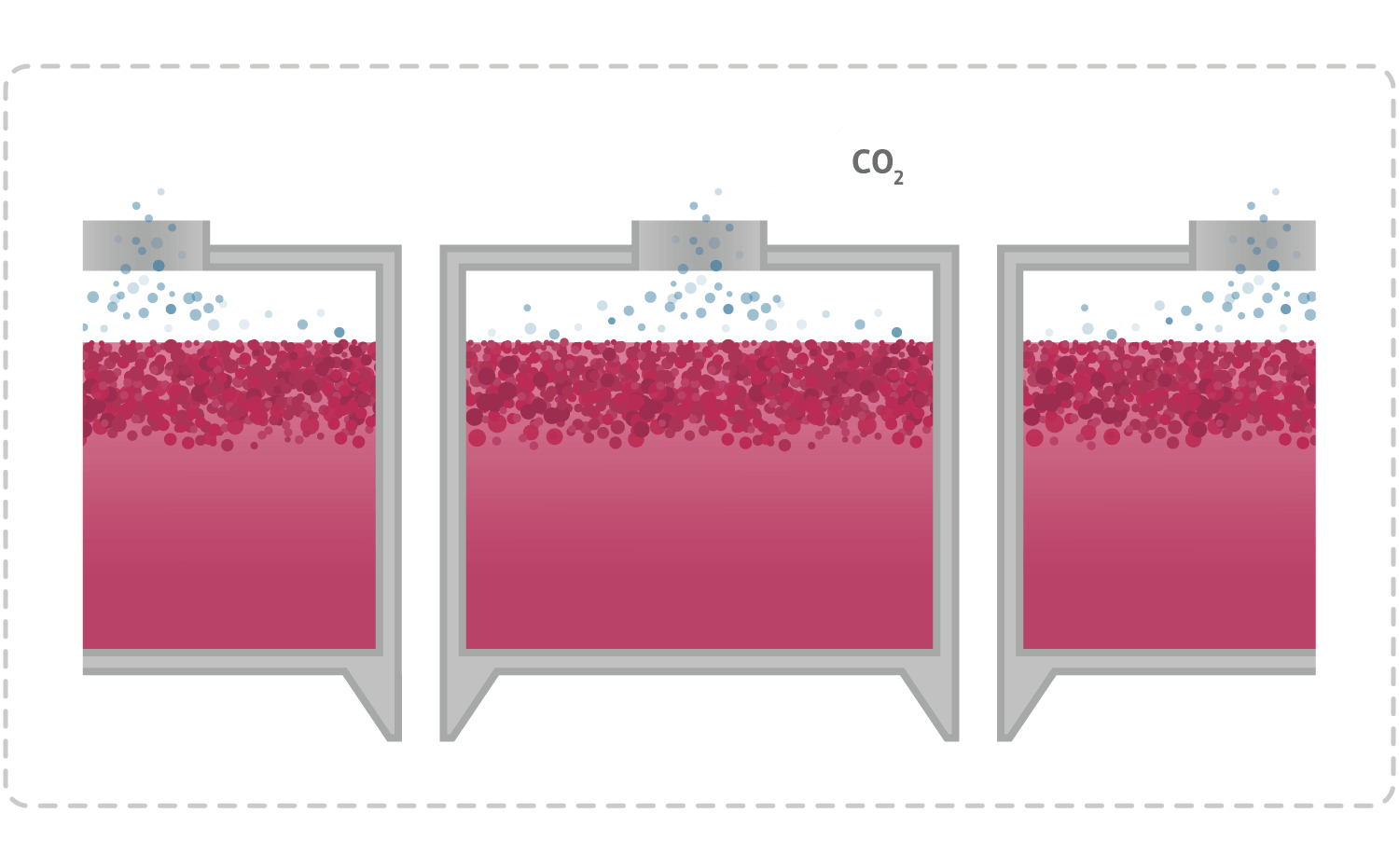

This is where yeasts transform juice into alcohol. The juicy must is moved from crushing or pressing into stainless steel tanks or oak barrels, where it can stay for about two weeks. With the absence of oxygen, yeast — wild occurring or inoculated — will convert the sugars of a wine grape to alcohol and carbon dioxide. (The more sugar in the grape, the higher the potential alcohol.)

When yeast cells die, they sink to the bottom of the fermentation tank and rest there with the skins, seeds and pulp fragments of the grape, creating the lees. Resting wine on the lees, or stirring the lees in the fermentation process, adds stability, body and flavor to the wine.

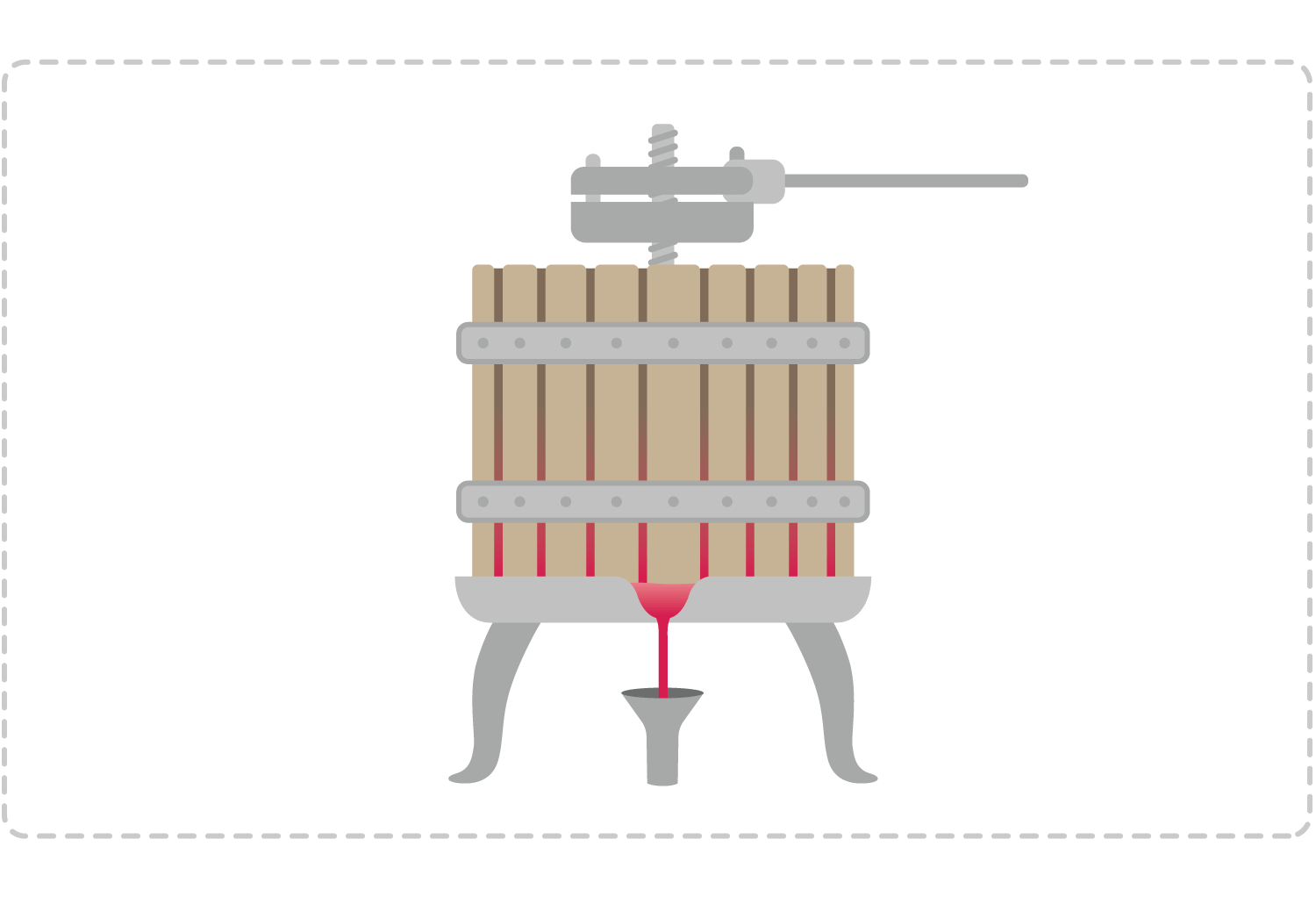

Pressing is the process of extracting the grape's juice. White wines are pressed before primary fermentation, reds typically after. Basket presses are one of the earliest forms of wine presses, and look like a basket or wine barrel with a disc at the top that presses down on the contents. Other press styles include a bladder press, membrane press, moving-head press and continuous press.

There is evidence of wine being stored in clay jugs in ancient Iran, Italy and France. It seems that winemakers through history have understood the simple fact that wine improves with time. Chemical processes take place during aging and react over time, creating different flavors as a wine matures.

Cask or barrel aging has become a romantic part of the winemaking process, even though it's really about instilling flavor and regulating temperature, humidity and light. Barrel aging dates back to the Roman Empire. Oak barrels were originally chosen for convenience — oak was prevalent, easy to shape and had tight grain for watertight storage. But it turned out that oak aging made the wine smooth and added pleasant flavors. Today, wines are typically aged in French and American oak. American white oak is considered more "oaky" and brings a vanilla aroma, where French oak contributions are more subtle and spicy.

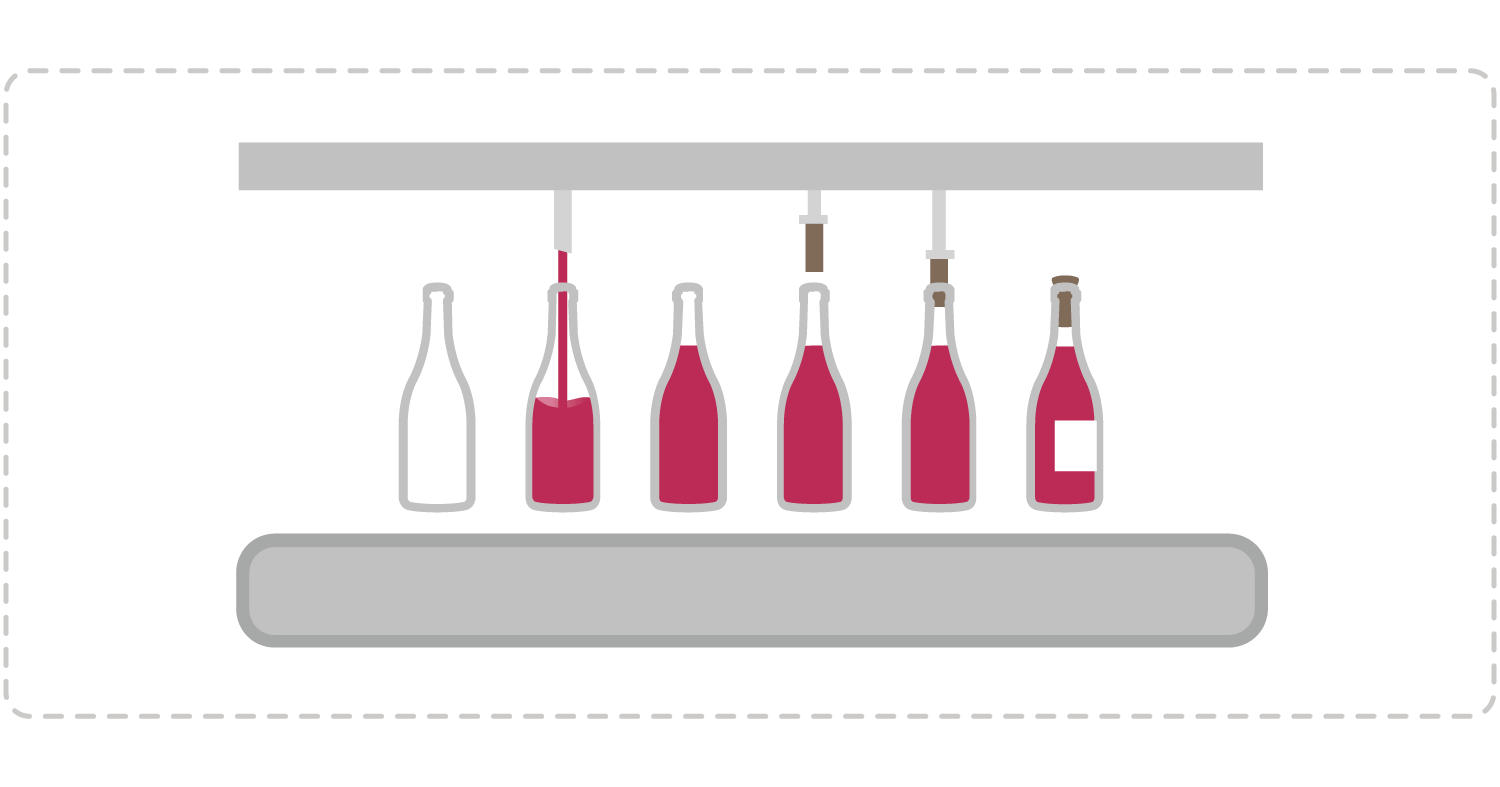

When wine is clear, stable and "finished," according to the winemaker, it's bottled. This can involve state-of-the-art machinery or simple methods. Bottling protects the wine — tinted bottles help keep out the light — and then time does the rest.

"We have a vision in mind, and then you react to the texture of your canvas and your colors — and what the vintage actually delivers — to achieve your vision."— Juan Muñoz Oca

For sparkling wines made in the champagne method, the wine undergoes a second fermentation in the bottle to add carbonation. The winemaker adds a mixture of sugar and yeast called the dosage, which creates a secondary fermentation in the bottle. These bottles are then racked and "riddled" (or turned on a regular basis as they age). Finally, the wine is "disgorged," which means the sediment or "lees" are collected in the neck of the bottle, frozen and expelled with pressure. They then add a small amount of sugar and still wine called the liqueur de tirage, which determines final sweetness. The wine is then corked and labeled.

Dessert wine is sweet. The making of a dessert wine varies dramatically, but there are generally three considerations. First are vineyard practices — late harvest, noble rot (botrytis), drying or freezing grapes. Second, stopping the fermentation by chilling and filtration. Third, if the fermentation isn't stopped, winemakers add sweetness back in by adding sugar or alcohol (typically brandy) before all the sugar is fermented, and remove water to concentrate the sugar.

Fortified wines are just that — fortified with extra spirits (usually grape spirits), beyond the level created in the natural winemaking process. Fortified wines included apéritif wines and dessert wines like port and sherry. The European Union calls them "liqueur wines." Some are sweet, some are dry, some are cheap, and some are expensive. The one thing they have in common is added spirits.

Fortified wines are sweet when alcohol is added during fermentation, because the added alcohol stops fermentation, and any unfermented sugar remains sugar. This results in port.

In contrast, fortified wines will be dry when the extra alcohol is added after fermentation. That's how sherry is made.